Solidity is the smart contract language of the Ethereum blockchain. It gets compiled into bytecode by the solc compiler. As one might expect, the compiled bytecode is intended to be executed by a computer - or rather, by the the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) distributed across all of the nodes participating in the Ethereum blockchain. As bytecode it lacks the context of the original source code that would make it human readable.

If all we have is the compiled Solidity bytecode of a smart contract, how do we know what it does? If there's documentation about what it does, great. But what if it's missing, incomplete, or we don't trust it? We can try running the smart contract, perhaps in a sandboxed environment, with various inputs and observe the outputs, but many smart contracts are complex and linked to other smart contracts or hard coded Ethereum addresses.

Here's a very simple example of Solidity, Test1.sol based on the example in the evmdis README:

pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract Test {

function double(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 2);

}

function triple(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 3);

}

function multiply(uint a, uint b) internal returns (uint) {

return a * b;

}

}pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract Test {

function double(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 2);

}

function triple(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 3);

}

function multiply(uint a, uint b) internal returns (uint) {

return a * b;

}

}pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract Test {

function double(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 2);

}

function triple(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 3);

}

function multiply(uint a, uint b) internal returns (uint) {

return a * b;

}

}And here it is assembled into bytecode with solc, the Solidity compiler:

$ solc --optimize --bin-runtime Test1.sol

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

======= Test1.sol:Test =======

Binary of the runtime part:

606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a723058202ea94b4449362217eab191a18d83fb2fb5e7c432a58cb3f0990ec4306e49b65a0029

$ solc --optimize --bin-runtime Test1.sol

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

======= Test1.sol:Test =======

Binary of the runtime part:

606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a723058202ea94b4449362217eab191a18d83fb2fb5e7c432a58cb3f0990ec4306e49b65a0029

$ solc --optimize --bin-runtime Test1.sol

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

======= Test1.sol:Test =======

Binary of the runtime part:

606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a723058202ea94b4449362217eab191a18d83fb2fb5e7c432a58cb3f0990ec4306e49b65a0029

We could try disassembling the bytecode, using a tool to translate each opcode into a human readable instruction. The result would still be fairly obtuse, with auto-generated variables names and concise, higher level constructs like loops and branches optimized into a verbose long form of assembly instructions.

$ solc --optimize --asm Test1.sol | head -n 50

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

======= Test1.sol:Test =======

EVM assembly:

mstore(0x40, 0x60)

jumpi(tag_1, iszero(callvalue))

invalid

tag_1:

tag_2:

dataSize(sub_0)

dup1

dataOffset(sub_0)

0x0

codecopy

0x0

return

stop

sub_0: assembly {

mstore(0x40, 0x60)

and(div(calldataload(0x0), exp(0x2, 0xe0)), 0xffffffff)

0xeee97206

dup2

eq

tag_2

jumpi

dup1

0xf40a049d

eq

tag_3

jumpi

tag_1:

invalid

tag_2:$ solc --optimize --asm Test1.sol | head -n 50

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

======= Test1.sol:Test =======

EVM assembly:

mstore(0x40, 0x60)

jumpi(tag_1, iszero(callvalue))

invalid

tag_1:

tag_2:

dataSize(sub_0)

dup1

dataOffset(sub_0)

0x0

codecopy

0x0

return

stop

sub_0: assembly {

mstore(0x40, 0x60)

and(div(calldataload(0x0), exp(0x2, 0xe0)), 0xffffffff)

0xeee97206

dup2

eq

tag_2

jumpi

dup1

0xf40a049d

eq

tag_3

jumpi

tag_1:

invalid

tag_2:$ solc --optimize --asm Test1.sol | head -n 50

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

======= Test1.sol:Test =======

EVM assembly:

mstore(0x40, 0x60)

jumpi(tag_1, iszero(callvalue))

invalid

tag_1:

tag_2:

dataSize(sub_0)

dup1

dataOffset(sub_0)

0x0

codecopy

0x0

return

stop

sub_0: assembly {

mstore(0x40, 0x60)

and(div(calldataload(0x0), exp(0x2, 0xe0)), 0xffffffff)

0xeee97206

dup2

eq

tag_2

jumpi

dup1

0xf40a049d

eq

tag_3

jumpi

tag_1:

invalid

tag_2:Not particularly easy to read.

Let's say we had the source code to a smart contract, and wanted to see if it was the same or similar to a compiled smart contract already on the blockchain. We could compile the source code to bytecode and perform a byte-by-byte comparison. This is unlikely to work in practice, as compilers tend to be nondeterministic between versions as optimizations are introduced. Even across two different executions on the same system, the resulting compiled bytecode can be different. Solidity has a goal of being deterministic, but hasn't always been. In the case of The DAO, there was an extensive effort undertaken to validate that the deployed DAO bytecode matched the source code made challenging by compiler non-determinism.

It's worth noting that Etherscan has a handy online facility to verify deployed smart contract bytecode vs. the source code. It allows selection of the full range of solc tags to try compiling against.

For offline smart contract verification, Nick Johnson's evmdis is a Solidity bytecode disassembler which takes a slightly different approach to disassembly. It implements a static analysis technique called abstract interpretation which simulates the execution of a sample of Solidity bytecode (here's another useful tutorial on the subject [PDF]). The evmdis readme has a good summary, but essentially it runs the program and tracks unique permutations of the program's stack. It also breaks the program into logical basic blocks and translates series of simples expressions into compound ones. The output is a more concise series of assembly instructions and jump labels organized into logical blocks, a kind of "summarized assembly", something a human can more easily analyze and reason about.

We learned a few lessons from playing around from this. First, there are some crucial options to pass to the Solidity compiler, solc, to make things work:

$ solc --version

solc, the solidity compiler commandline interface

Version: 0.4.11-develop.2017.4.26+commit.c3b839ca.Darwin.appleclang

$ solc --bin-runtime --optimize -o . Test1.sol

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

# Note that solc strips trailing numbers off of the Solidity source filename when naming output files.

$ cat Test.bin-runtime

606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a72305820d37021dfa166ba3f7f8d592355b8a9313292e2e008f24cbd45bf273c269f059f0029$

$ solc --version

solc, the solidity compiler commandline interface

Version: 0.4.11-develop.2017.4.26+commit.c3b839ca.Darwin.appleclang

$ solc --bin-runtime --optimize -o . Test1.sol

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

# Note that solc strips trailing numbers off of the Solidity source filename when naming output files.

$ cat Test.bin-runtime

606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a72305820d37021dfa166ba3f7f8d592355b8a9313292e2e008f24cbd45bf273c269f059f0029$

$ solc --version

solc, the solidity compiler commandline interface

Version: 0.4.11-develop.2017.4.26+commit.c3b839ca.Darwin.appleclang

$ solc --bin-runtime --optimize -o . Test1.sol

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

# Note that solc strips trailing numbers off of the Solidity source filename when naming output files.

$ cat Test.bin-runtime

606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a72305820d37021dfa166ba3f7f8d592355b8a9313292e2e008f24cbd45bf273c269f059f0029$

If we had provided just the --bin flag instead of --bin-runtime, solc would have automatically wrapped our smart contract with code to load the smart contract itself onto the blockchain. If we then try to simulate execution of this bytecode with evmdis, we don't get any useful output because the we just end up running the ‘loader' code and not the contained smart contract.

The --optimize flag is like the -O flag to gcc, it tries to optimize the compiled code.

The -o . flag specifies the current directory as the output directory. Otherwise it would be to stdout with some extra output that we'd need to strip off.

Next we download and install evmdis:

$ go get github.com/Arachnid/evmdis

$ go install github.com/Arachnid/evmdis/evmdis

$ which evmdis

/Users/curvegrid/golang/bin/evmdis

$

$ go get github.com/Arachnid/evmdis

$ go install github.com/Arachnid/evmdis/evmdis

$ which evmdis

/Users/curvegrid/golang/bin/evmdis

$

$ go get github.com/Arachnid/evmdis

$ go install github.com/Arachnid/evmdis/evmdis

$ which evmdis

/Users/curvegrid/golang/bin/evmdis

$

evmdis expects the raw hex data (ASCII base-16 representation of Solidity bytecode) output by solc to be piped to it.

$ cat Test.bin-runtime | evmdis > Test1.disasm

$ cat Test1.disasm

# Stack: []

0x4 MSTORE(0x40, 0x60)

0x13 PUSH(CALLDATALOAD(0x0) / 0x2 ** 0xE0 & 0xFFFFFFFF)

0x19 DUP1

0x1D JUMPI(:label0, POP() == 0xEEE97206)

$ cat Test.bin-runtime | evmdis > Test1.disasm

$ cat Test1.disasm

# Stack: []

0x4 MSTORE(0x40, 0x60)

0x13 PUSH(CALLDATALOAD(0x0) / 0x2 ** 0xE0 & 0xFFFFFFFF)

0x19 DUP1

0x1D JUMPI(:label0, POP() == 0xEEE97206)

$ cat Test.bin-runtime | evmdis > Test1.disasm

$ cat Test1.disasm

# Stack: []

0x4 MSTORE(0x40, 0x60)

0x13 PUSH(CALLDATALOAD(0x0) / 0x2 ** 0xE0 & 0xFFFFFFFF)

0x19 DUP1

0x1D JUMPI(:label0, POP() == 0xEEE97206)

Still not super compact but more so than the raw decoded assembly.

Let's try making a trivial change to our test smart contract, compiling and comparing it. We'll put this in Test2.sol.

$ cat Test2.sol

pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract Test {

function double(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 2);

}

function triple(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 4);

}

function multiply(uint a, uint b) internal returns (uint) {

return a * b;

}

}

# because solc strips trailing numbers off of source code file names when it outputs them

$ mv Test.bin-runtime Test1.bin-runtime

$ solc --bin-runtime --optimize -o . Test2.sol

$ mv Test.bin-runtime Test2.bin-runtime

$ diff Test1.bin-runtime Test2.bin-runtime

1c1

< 606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a72305820d37021dfa166ba3f7f8d592355b8a9313292e2e008f24cbd45bf273c269f059f0029

\ No newline at end of file

---

> 606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260046094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a723058209a386daa605597ff9e13819e908aab2cafdc814ff67c34d318c4e7048eb5b9360029

\ No newline at end of file$ cat Test2.sol

pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract Test {

function double(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 2);

}

function triple(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 4);

}

function multiply(uint a, uint b) internal returns (uint) {

return a * b;

}

}

# because solc strips trailing numbers off of source code file names when it outputs them

$ mv Test.bin-runtime Test1.bin-runtime

$ solc --bin-runtime --optimize -o . Test2.sol

$ mv Test.bin-runtime Test2.bin-runtime

$ diff Test1.bin-runtime Test2.bin-runtime

1c1

< 606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a72305820d37021dfa166ba3f7f8d592355b8a9313292e2e008f24cbd45bf273c269f059f0029

\ No newline at end of file

---

> 606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260046094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a723058209a386daa605597ff9e13819e908aab2cafdc814ff67c34d318c4e7048eb5b9360029

\ No newline at end of file$ cat Test2.sol

pragma solidity ^0.4.0;

contract Test {

function double(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 2);

}

function triple(uint a) returns (uint) {

return multiply(a, 4);

}

function multiply(uint a, uint b) internal returns (uint) {

return a * b;

}

}

# because solc strips trailing numbers off of source code file names when it outputs them

$ mv Test.bin-runtime Test1.bin-runtime

$ solc --bin-runtime --optimize -o . Test2.sol

$ mv Test.bin-runtime Test2.bin-runtime

$ diff Test1.bin-runtime Test2.bin-runtime

1c1

< 606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260036094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a72305820d37021dfa166ba3f7f8d592355b8a9313292e2e008f24cbd45bf273c269f059f0029

\ No newline at end of file

---

> 606060405263ffffffff60e060020a600035041663eee972068114602a578063f40a049d14604c575bfe5b3415603157fe5b603a600435606e565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b3415605357fe5b603a6004356081565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b600060798260026094565b90505b919050565b600060798260046094565b90505b919050565b8181025b929150505600a165627a7a723058209a386daa605597ff9e13819e908aab2cafdc814ff67c34d318c4e7048eb5b9360029

\ No newline at end of fileNot very enlightening, although we can see there are differences. Let's try diffing the evmdis output.

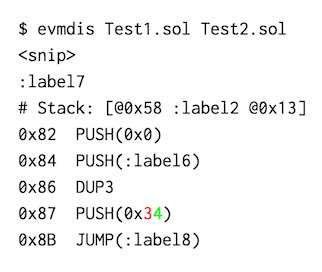

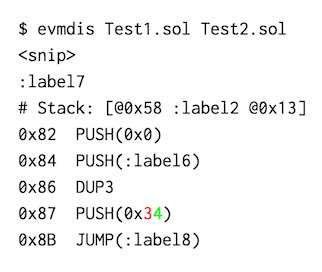

$ cat Test2.bin-runtime | evmdis > Test2.disasm

$ diff Test1.disasm Test2.disasm

:label7 :label7

# Stack: [@0x58 :label2 @0x13] # Stack: [@0x58 :label2 @0x13]

0x82 PUSH(0x0) 0x82 PUSH(0x0)

0x84 PUSH(:label6) 0x84 PUSH(:label6)

0x86 DUP3 0x86 DUP3

0x87 PUSH(0x3) | 0x87 PUSH(0x4)

0x8B JUMP(:label8) 0x8B JUMP(:label8)

$ cat Test2.bin-runtime | evmdis > Test2.disasm

$ diff Test1.disasm Test2.disasm

:label7 :label7

# Stack: [@0x58 :label2 @0x13] # Stack: [@0x58 :label2 @0x13]

0x82 PUSH(0x0) 0x82 PUSH(0x0)

0x84 PUSH(:label6) 0x84 PUSH(:label6)

0x86 DUP3 0x86 DUP3

0x87 PUSH(0x3) | 0x87 PUSH(0x4)

0x8B JUMP(:label8) 0x8B JUMP(:label8)

$ cat Test2.bin-runtime | evmdis > Test2.disasm

$ diff Test1.disasm Test2.disasm

:label7 :label7

# Stack: [@0x58 :label2 @0x13] # Stack: [@0x58 :label2 @0x13]

0x82 PUSH(0x0) 0x82 PUSH(0x0)

0x84 PUSH(:label6) 0x84 PUSH(:label6)

0x86 DUP3 0x86 DUP3

0x87 PUSH(0x3) | 0x87 PUSH(0x4)

0x8B JUMP(:label8) 0x8B JUMP(:label8)

The difference here is fairly clear. It's worth noting that at this point we were getting tired of piping, mv'ing and diffing files. We extended evmdis so you can now just do this:

Coloured diffing thanks to the go-diff package.)

Feel free to play around with our modifications. You can pass in Solidity, which will automatically be compiled with solc, or bytecode in ASCII hex format. It retains the original evmdis functionality of parsing stdin, if desired. If one input is provided, it will be disassembled and displayed. If two inputs are provided, they will be disassembled and compared. Optionally, the bytecode and source Solidity (if available) can be compared as well.

$ evmdis -h

Usage of evmdis:

evmdis [] [ []]

Options:

-cmpasm

Compare disassembled solidity bytecode. (default true)

-cmpbc

Compare solidity bytecode.

-cmpsol

Compare solidity source code (if available).

-patch

Show differences in patch format instead of by colour.

-solc string

Path to solc Solidity compiler. (default "solc")

-solcoptions string

Options to pass to solc. (default "--optimize --bin-runtime")

-stdin

Force stdin as one of the input methods. Required if stdin desired in addition to a single command line parameter passed

$ evmdis -h

Usage of evmdis:

evmdis [] [ []]

Options:

-cmpasm

Compare disassembled solidity bytecode. (default true)

-cmpbc

Compare solidity bytecode.

-cmpsol

Compare solidity source code (if available).

-patch

Show differences in patch format instead of by colour.

-solc string

Path to solc Solidity compiler. (default "solc")

-solcoptions string

Options to pass to solc. (default "--optimize --bin-runtime")

-stdin

Force stdin as one of the input methods. Required if stdin desired in addition to a single command line parameter passed

$ evmdis -h

Usage of evmdis:

evmdis [] [ []]

Options:

-cmpasm

Compare disassembled solidity bytecode. (default true)

-cmpbc

Compare solidity bytecode.

-cmpsol

Compare solidity source code (if available).

-patch

Show differences in patch format instead of by colour.

-solc string

Path to solc Solidity compiler. (default "solc")

-solcoptions string

Options to pass to solc. (default "--optimize --bin-runtime")

-stdin

Force stdin as one of the input methods. Required if stdin desired in addition to a single command line parameter passed

We also added the ability to pass in an Ethereum smart contract address, which will download the bytecode and use that as an input. However, we are not making these modifications public as they rely on scraping a third party website and we don't want to be a source of noise for them.

It does allow us to come back to something we mentioned earlier in this post: comparing the deployed DAO smart contract to its source code.

$ evmdis TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413

2017/05/10 16:22:36 Could not parse source 'TheDAO.sol': Problem compiling solidity: exit status 1

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

:89:52: Error: Expected token Semicolon got 'RBrace'

modifier noEther() {if (msg.value > 0) throw; _}

$ evmdis TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413

2017/05/10 16:22:36 Could not parse source 'TheDAO.sol': Problem compiling solidity: exit status 1

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

:89:52: Error: Expected token Semicolon got 'RBrace'

modifier noEther() {if (msg.value > 0) throw; _}

$ evmdis TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413

2017/05/10 16:22:36 Could not parse source 'TheDAO.sol': Problem compiling solidity: exit status 1

Warning: This is a pre-release compiler version, please do not use it in production.

:89:52: Error: Expected token Semicolon got 'RBrace'

modifier noEther() {if (msg.value > 0) throw; _}

Ah, The DAO was deployed in April 2016 and compiled using solc version v0.3.1-2016-04-12-3ad5e82, whereas we're on solc 0.4.11. It appears there have been backward and forward incompatible changes to Solidity since then. For example:

$ solc-0.3.2 Test1.sol

Test1.sol:1:1: Error: Expected import directive or contract definition.

pragma solidity ^0.3.0;

$ solc-0.3.2 Test1.sol

Test1.sol:1:1: Error: Expected import directive or contract definition.

pragma solidity ^0.3.0;

$ solc-0.3.2 Test1.sol

Test1.sol:1:1: Error: Expected import directive or contract definition.

pragma solidity ^0.3.0;

For The DAO, we can use an earlier version of solc with our modified version of evmdis:

# Per the above, the evmdis modifications we've published don't include the ability demonstrated here to pass an Ethereum smart contract address in order to prevent this from becoming a source of noise against a third party website

$ evmdis --solc /usr/local/bin/solc-0.3.2 TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413

# Stack: []

0x4 MSTORE(0x40, 0x60)

0xA JUMPI(:label0, !CALLDATASIZE())

# Stack: []

0x13 PUSH(CALLDATALOAD(0x0) / 0x2 ** 0xE0)

0x19 DUP1

0x1E JUMPI(:label2, POP() == 0x13CF08B)

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x1F DUP1

0x29 JUMPI(:label3, 0x95EA7B3 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x2A DUP1

0x34 JUMPI(:label5, 0xC3B7B96 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x35 DUP1

0x3F JUMPI(:label6, 0xE708203 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

# How many lines?

$ evmdis --solc /usr/local/bin/solc-0.3.2 TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413 | wc -l

5540# Per the above, the evmdis modifications we've published don't include the ability demonstrated here to pass an Ethereum smart contract address in order to prevent this from becoming a source of noise against a third party website

$ evmdis --solc /usr/local/bin/solc-0.3.2 TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413

# Stack: []

0x4 MSTORE(0x40, 0x60)

0xA JUMPI(:label0, !CALLDATASIZE())

# Stack: []

0x13 PUSH(CALLDATALOAD(0x0) / 0x2 ** 0xE0)

0x19 DUP1

0x1E JUMPI(:label2, POP() == 0x13CF08B)

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x1F DUP1

0x29 JUMPI(:label3, 0x95EA7B3 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x2A DUP1

0x34 JUMPI(:label5, 0xC3B7B96 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x35 DUP1

0x3F JUMPI(:label6, 0xE708203 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

# How many lines?

$ evmdis --solc /usr/local/bin/solc-0.3.2 TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413 | wc -l

5540# Per the above, the evmdis modifications we've published don't include the ability demonstrated here to pass an Ethereum smart contract address in order to prevent this from becoming a source of noise against a third party website

$ evmdis --solc /usr/local/bin/solc-0.3.2 TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413

# Stack: []

0x4 MSTORE(0x40, 0x60)

0xA JUMPI(:label0, !CALLDATASIZE())

# Stack: []

0x13 PUSH(CALLDATALOAD(0x0) / 0x2 ** 0xE0)

0x19 DUP1

0x1E JUMPI(:label2, POP() == 0x13CF08B)

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x1F DUP1

0x29 JUMPI(:label3, 0x95EA7B3 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x2A DUP1

0x34 JUMPI(:label5, 0xC3B7B96 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

0x35 DUP1

0x3F JUMPI(:label6, 0xE708203 == POP())

# Stack: [@0x13]

# How many lines?

$ evmdis --solc /usr/local/bin/solc-0.3.2 TheDAO.sol 0xbb9bc244d798123fde783fcc1c72d3bb8c189413 | wc -l

5540We can see from the output there are a lot of changes, across a total of 5540 lines of disassembled code. This is a lot to look at, however, far less than the raw disassembly:

$ solc-0.3.2 --asm --optimize TheDAO.sol | wc -l

21513

$ solc-0.3.2 --asm --optimize TheDAO.sol | wc -l

21513

$ solc-0.3.2 --asm --optimize TheDAO.sol | wc -l

21513

We're going to leave things here for now. One challenge you might have in testing out evmdis or solc against existing Solidity source code is finding a runnable copy of a particular solc version. We spent a lot of time getting solc 0.3.2 working as part of this exercise, and it's the basis of our next post.